Whittlesey is a pleasant little market town in the north-west of the Isle of Ely, with two medieval churches: St Mary in the very centre, and St Andrew a little way further out. The town has the slightly run-down feeling common to many market towns in an era when out-of-town Tesco stores are leeching the lifeblood from weekly markets and high-street shops. We visited on a grey Saturday in August, and the streets were full of bored teenagers, sitting around dreaming of the big city (or Peterborough, as it’s known to the rest of us).

Perhaps it’s for this reason that the church of St Mary has the only locked churchyard we’ve come across in Cambridgeshire. (Well, we also found Bassingbourn locked, but I’ve since been assured that that was a fluke). I can understand the PCC’s reasoning – even aside from moral disapproval, there’s a public health issue with letting people use a churchyard for their drug addictions – but it’s still sad to see.

This church sits in an interesting location. It overlooks the market, and to the north, south and east it is so hemmed in by buildings that it is hard to see all of the exterior at once. That doesn’t especially matter though because the only view worth seeing is that from the west. There, the churchyard is wide and open, so one can stand back and enjoy the finest church tower in Cambridgeshire.

I’ve thought long and hard about which tower to give that accolade, and I’m aware that I can get overtaken with momentary enthusiasms for buildings that wane with calm reflection. Nevertheless: this tower is taller than Willingham, more beautiful than Leverington, more majestic than Great St Mary in Cambridge and more richly decorated than St Peter & Paul in Wisbech.

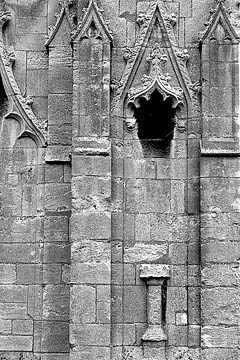

The base of the tower is decorated with niches, blind panelling and small buttresses with spires on the top, with the west door being surrounded by a particular sumptuous projecting ogee arch. Above that, there is a big west window, and even more surface decoration. The corners are clasp-buttressed at the base, then cross-buttressed at the first stage, clasp-buttressed again at the second stage and given diagonal buttresses around the bell-chamber.

From these corners rise four pinnacles, with slender flying buttresses supporting a beautiful crocketted spire. We approached Whittlesey from the north, and could see this spire almost from Thorney: seeing the light shine through the three tiers of windows was especially beautiful. There is also a stair turret tucked away on the northern side of the east face. It rises to roughly half the height of the parapet, and is itself richly decorated: it is octagonal, with the faces covered in blind panelling and the top capped with a little Tudor turret.

The body of the church has very little to match this; the 14th century porch on the south side is quite impressive and has two rib-vaulted bays, but it is very plain by comparison.

While I was gasping at the west tower, Mark telephoned the rector to ask if we could pick up a key. As it happened, he was just about to come over to the church anyway to put up some notices, so he was able to let us in (and then, for the most part, left us alone to wander, which was very much appreciated – it can be difficult to make notes properly with someone hanging over your shoulder).

The interior was bigger than I expected, but it has a peculiarly jumbled feel to it: every corner seems to be filled with different types of seats, or tables, or monuments, so that there’s no sense of grand scale. This impression is also due to the building history of the church, for there was no big rebuilding of the nave to match the construction of the west tower in the 15th century.

The oldest nave arcades, those on the north side, date from the mid 13th century, having been built after a fire in 1244 along with the north aisle and the western half of the chancel.

Then, in the 14th century, the nave was extended one bay to the west: the new work is slightly different in style to the old, and the join is a bit awkward, with the pier containing quite a bit of wall preserved between the responds. At the same time, the south aisle was built: an unusually wide space, with two decent sized west windows side by side. Finally, at the time of the construction of the tower, the chancel was lengthened somewhat to the east.

As might be expected, the best bit of the interior is the tower. The arch is extremely lofty, and decorated with niches and panelling on the responds. The space within is open up to the bell-stage, and is surmounted by an elegant tierceron vault with a large circular trapdoor in the middle. At the base of the tower sits the dado of the old rood screen, which retains some of its original paint and looks very hefty.

The chancel arch from which it was taken is not especially wide, but the loft must have been quite substantial, for the upper doorway of the rood stair is almost full height. I did like the rood stair, incidentally. It is accessed via a doorway to the south of the chancel arch, and then winds upon within a little internal turret in the north-west corner of the south chapel, complete with small openings to give light onto the staircase. Somewhere near the top it branches, and leads to two doorways: the central door already mentioned, and another doorway (if anything, even bigger) leading into the south aisle. Presumably there was a big parclose screen, which would suggest that the south chapel must have belonged to a rich guild.

All that remains in that south chapel now is a raised platform at the east end, below which is a vault containing some old graves and the church’s oil boiler. The vicar, as we were leaving, told us an amusing story about how various members of the church council had hoped to open up the vaults (which run all along the length of the south aisle) and to charge tourists for entry: the plan was quickly abandoned when it was discovered that the said vaults are cramped, architecturally uninterested and distinctly lacking in picturesque coffins or skeletons.

The chancel, despite being rather large, feels cramped: even more than the nave and south aisle, it is full of clutter: the only respite is the beautiful blind panelling on the frame of the east window, built in the 15th century to match the tower arch. The walls are filled with wall-memorials, from the 16th century onwards.

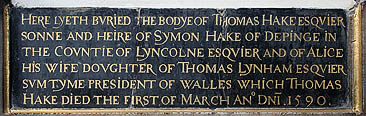

Most of them are uninteresting sober 19th century things, but I did like one on the north wall. It is an Elizabethan wall-plate commemorating one Thomas Hake and his wife.

Like many such monuments, it comprises an elaborate painted alabaster frame around two round-topped niches intended for Thomas and his wife. At some point, though, the monument was damaged and the figures lost. It is now set much deeper into the wall, and the two niches are filled with blank white plaster. It’s an elegant memorial, anyway.