This is a grand church. Unusually for East Anglia, the reason for its grandeur is not that it is huge. Many churches are impressive by virtue of their scale alone: this is especially true in Suffolk and Norfolk, but also here in Cambridgeshire at (for example) Cottenham and Swavesey. The church at Fordham isn’t especially large, by contrast. It is, however, a splendidly dramatic piece of architecture.

For a start, it is tall: tall aisles, and clerestory, with battlements decorating the edges and emphasising the fortress-like proportions. Above the east end of the nave are a pair of decorative turrets: at first I saw only one, and thought that it might be for a sanctus bell, but further reflection (and discovery of the second) made me think that they are purely for decoration: more evidence of lavishness. The aisles extend eastwards along the sides of the chancel; this means that there’s not much distinct sign of the latter on the exterior of the building, with the east end instead being broad and stocky. The windows throughout are mostly big and Perpendicular, with stonework that has the crisp look of a Victorian restoration.

The tower is splendid: a lofty Suffolky affair with battlements and a polygonal stair turret on the northwest corner. The view from the west is especially grand, with the lower part of the tower filled with a big west window.

Entry to the church is now through the north, but there is also a disused south porch. The doorway looks restored, but it is obviously old. The responds on either side are decorated with crenellations, and above the opening is a decorated niche. The canopy has now gone, but the shape of it survives.

The thing that really stands out on the exterior is the Decorated Lady Chapel that sits over where the north porch would usually be, towards the northwest corner of the nave. It is an intriguing thing: entry to the church is through a door in the lower floor, and the space above is lit by very large windows. This sort of thing is tremendously unusual in a parish church. At Leverington the porch is very grand and has an elaborate parvise above the entrance, but there’s no suggestion that it was ever a chapel, and it is much smaller. It is most like Prior Crauden’s chapel in Ely; I wonder how it ended up being built here?

Much of the church is Decorated like the chapel, dating from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, though there are survivals from the twelfth century and parts that were rebuilt in the fifteenth. There was also a drastic restoration in the 1860s and 70s, so don’t come here expecting a pure example of a single period. (Then again, you’d be mad to go to most churches expecting that, both because such purity is very rare and because part of the fun is watching the interplay between the centuries).

So, going inside, what do we find? Well, the space under the chapel is as nice as one would expect, though it was being used to store assorted parochial detritus when we visited. There are two central pillars, and these support a low stone vault, almost like a crypt. The church guide suggests that this might too have been a chapel originally, dedicated to St Thomas à Becket. There is a medieval image of the saint in one of the north windows, which is also the oldest glass in the church: as you will see, the Victorian glazers had a field day in the rest of the building.

Passing through into the main church, there is at first an impressive feeling of space: the nave, of five bays, is tall, and larger than it looks from the outside. After that first impression of space, though, the effect of the 19th century decoration causes the walls to close in a bit. For a decent sized building, with lots of windows, this is depressingly dark. I quite liked the Victorian aisle windows (of which more anon), but they didn’t let in much light. The clerestory is glazed in an inexplicable blue colour which makes the nave feel like an underwater cavern, and the walls around the nave arcades are painted with a sombre Morris-esque design. I tried to be enthusiastic, but it’s all a bit gloomy, and I felt distinctly claustrophobic.

Still, there was plenty to look at and appreciate. The font, for example, is a fine thing: very substantial, with an octagonal bowl and shallow carvings of arches on the faces. Nearly, in the northwest corner of the north aisle, there are two Norman lancets: they are now fossilised, and would only open onto the undercroft of the Lady Chapel, but they are a remnant of an earlier church on this site. Their location sort-of implies that the Norman building was also aisled, which is impressive, and suggests that Fordham has always had an imposing church. Why was this, I wonder? There was a small priory here; a daughter house of the Gilbertine abbey of Sempringham in Lincolnshire, but it wasn’t founded until the thirteenth century and was never very big, so monastic patronage can hardly be the explanation. Nor are there any signs of a powerful local gentry family who might have provided the money. It’s all most mysterious.

|

One rather good Victorian addition is the gallery which connects the Lady Chapel to the north aisle. Originally it would have been quite separate, and accessed via a staircase from the undercroft, but in 1864 the Rector dismantled the wall and provided a new entry from the aisle. The staircase is now modern, and the chapel is screened off by a Victorian arcade and glass partitions. We went up and had a look: it now seems to be a venue for the Sunday school, and is a lovely space. The crown post roof is Victorian, but they have left the windows full of clear glass, and it’s by far the lightest part of the church.

From the top of the stairs, one also gets an interesting view out through the nave. It isn’t often that one gets to see a church from about halfway up an aisle wall. Squinting so as to ignore the wall-painting, I decided that I really rather liked the masonry here. The arcades are carved nice and crisply, and the corbels supporting the roof are lots of crowned heads with lovely beards. The piers are also of different ages: the easternmost bay is from the thirteenth century, but from there westwards this is Decorated work of the early fourteenth; perhaps it was rebuilt so as to coincide with the new chapel. Fifteenth-century Perpendicular additions include the clerestory and the south porch. The latter was open to the church, and I wandered in to have a look. It is lined with benches, and has blind panelling rising from the back along the walls, the two middle panels having windows about halfway up.

The benches in the nave have lots of poppy heads, Most of them don’t look medieval, but some do. In the south aisle we found a bishop who looked decidedly well-worn, and various others looked like they might be older survivals that have been included as part of a more recent set. I especially liked one that we found in the middle of the church, where there is a depiction of someone playing a very long, thin stringed instrument.

I would mention the grim wall-paintings in the tower space, and the incongruous rose window that has been inserted over the chancel arch, but you’d (probably with some justification) accuse me of Victorian-bashing. So, I’ll demonstrate my freedom from prejudice by hurrying on to talk about the chancel soon. Before I do, it’s worth mentioning the aisle windows, because despite their failure to provide much light, they are actually quite nice. They are a variety of scenes from the Bible, and are of good quality: the figures sit on fine dark blue backgrounds, with nice architectural details over the top. The best one was the easternmost window in the south aisle, which depicts various passages from the Book of Samuel; this one was dedicated to Corporal Arthur Robert Townsend, who died in Johannesburg in 1903, a victim of the Boer War.

The chancel, for all that the building itself is Early English, is another example of over-exuberant Victorian restoration, this time from 1871. Unlike the nave, though, the effect here is much better. The wall-paintings are splendid: unlike the bland patterning further west, here we have a distinguished company of saints and prophets. (Scurrilous commentators might say that the style is just a little bit too chocolate-box, but I’ll forebear to say such things). On the north wall stand St Etheldreda, St Alban, St Stephen, Isaiah, David, St John the Baptist and St Peter; on the south we have St Paul, St James, Daniel, St John the Evangelist, St Perpetua, St Edmund and St Augustine. I was somewhat confused to see that St Edmund is given a very grey beard. This is both inaccurate (he died before he was thirty) and very idiosyncratic, since St Edmund is usually treated by painters as a home-grown version of St Sebastian, to be shown as a handsome young man peppered with arrows. (Much better to have patriotic English homoeroticism in your church art, don’t you think?)

Some of the furniture in the chancel is medieval. The rear choir stalls are 14th century and have some misericords. Not especially good misericords, mind you, but misericords nonetheless. The panelling around the stalls is thought to come from the rood screen. Also, although the piscina and sedilia were rebuilt in the restoration, it was done with medieval stone found by the workmen in the course of their activities. So, the piscina has old-looking dogtooth decoration around its arch, and the sedilia have the thick tube-like moulding over the top that one sees in places like Histon.

The single best thing the Victorians did for the church was the chancel roof, I think. It’s quite gorgeous: there are angels everywhere on the wall plates and tie-beams, and the whole thing is painted richly in greens, reds and golds, with stencilling on the rafters providing additional richness. I find it paradoxical that there is such a contrast between this workmanship and the dull painting in the nave and tower. True, a late 19th century Anglo-Catholic would probably deem it appropriate to have the chancel more richly decorated than the nave, but that alone cannot account for the difference in spirit between the spaces: the chancel rings with celebration: the joy of craftsmanship in the service of religion. There’s little of joy or celebration in the nave, I think.

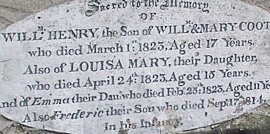

Musing on this, we left, and I took a walk around the churchyard while Mark finished taking his photographs. It’s a good churchyard, filled with cedars and pines. A little way to the south of the chancel, I found a rather dilapidated chest tomb, and paused to read it. Once upon a time there were Doric columns on the corners, but only the northeastern one survives, and the stone panels between are starting to crumble. The inscriptions tell a sad story, commemorating the four children of William and Mary Coot. Frederick Coot died in 1814 in his infancy, and then in 1823 the poor parents suffered a triple blow: their son William Henry died at the age of 17, and their daughters Louisa Mary and Emma followed shortly afterwards, aged 15 and 11 respectively. What a world of pain the simple inscription hides away, and how odd it is that the death of our loved ones is distilled down into these terse letters, slowly softening into illegibility through years of rain. Churchyards are haunted places, but I think their ghosts are not the people who lie quiet under the soil. Rather, they are filled with the shades of the mourners: the weeping widows, the keening parents and the dark-eyed, uncomprehending children.

SS Peter and Mary Magdalene is kept open.