Holy Trinity must be one of the most recognisable churches in Cambridgeshire. The village sits on a rise of land to the north of the A14, and travellers in either direction on that road have a fine view of it, sailing along the tops of the fields. Given that it's also a very fine building - one of the four in Cambridgeshire that Simon Jenkins rated with three stars, and definitely worth it - it's rather sad that it's so very difficult to get into.

** update: The church is (as of July 2018) open during daylight hours ** so the next bit is now historical! Mark and I have stopped in about five or six times over the last three years. Initially, there wasn't any information about keyholders at all, just a rather forbiddingly locked porch. Latterly, there has been a sign telling us that we could get a key from the garage - though since we were each time passing through on a Sunday, or relatively late in the evening, that wasn't much use. Holy Trinity is a big church, clearly visible and in the middle of the village - why can't they keep it open for visitors?

One of the problems with a church being habitually locked is that it projects a certain image: an indifference to the lives going on around it, and a turning-away from the world.

This tends to make people feel that the church is irrelevant - which, if it behaves like this, it soon will be - and tends to irritate people like me, who feel that they ought to be kept open, for reasons both religious and historical. If a church is the heart of a village, then when it's kept locked, it's just a lump of stone. Do we want all our villages to be like Margaret Thatcher? Plainly not.

I already felt irritated on our most recent visit, and practised slightly overblown rants in my head as I stomped up the gravel path to the porch… and found it open! This is a wonderful development, and I hope it indicates that Bottisham's heart has been properly opened once more. I'm quite happy to give the pleasures of tedious sermonising if the reason is lots of churches becoming unlocked. Immediately feeling more cheerful, I hurried inside.

I'd be getting things muddled, though, if I didn't dwell a little on the exterior. The first feature that one notices is the excellent galilee porch on the west face of the tower. It's a big structure, taller than most porches, and must have been modelled on Ely: originally, it had a tall western arch rising almost to the full height of the west face.

Subsequently that big west arch was filled in with rubble and flint, though it couldn't have been very much later by the look of the smaller doorway and the new window and niche that were inserted above it, which are still certainly medieval. The window suggests that the grandeur of the galilee didn't quite warrant wasting the space above the entrance, and that a parvise was therefore inserted (presumably to provide the priest a place to live, as usual).

The porch, and the somewhat squat tower to which it is attached, are both from the 13th century. The rest of the church has contemporary bits and bobs, but much of it was rebuilt in the following century: and the impression one gets from the exterior is of uncommonly good Perpendicular craftsmanship.

Holy Trinity is, unusually for this area, mostly built of stone, and the big windows glint darkly. The windows of the aisles are separated by buttresses, each decorated with false gables and linked with a string course at eye level; and beneath the windows of the south aisle were broad shallow blind arches, looking like tomb niches, and filled in with decorative flintwork. More than any other church in the county, Holy Trinity is like a reliquary.

Entry now is, for reasons that will become clear, through the south porch. It's not as unusual as the galilee, of course, but it's still rather nice: a big square one, with sets of 17th century windows in square frames on either side, and an old niche over the main arch. It's balanced by a north porch, though the latter has been bricked in to form a vestry or storeroom of some sort.

The interior matches the exterior in grandeur. The nave is five bays long, with deeply moulded arches decorated with many soft rolls of stone. The piers are likewise elaborate: four round shafts bunched together in a quatrefoil, with thin blade-like shapes wedged in between them, and round capitals at the top. These piers - and, indeed, all the decorative stonework in the church - are made of a wonderful dove grey stone, with an unusual soft lustre to it.

I've seen something similar elsewhere - the beautiful blind arcades at Histon are made of it, and the sedilia at Teversham - but never used on such lavish scale as here. It also appears in the clerestory (which is contemporary with the piers, rather than a later addition as often happens) and in the tracery of the aisle windows, and in a string course running along the aisle walls about eight feet from the ground, looping upwards to frame the broad Decorated windows. It's all fine stuff.

In the south wall, I found myself puzzled by the presence of the same shallow arches in the bottom of the walls below each window. The positions exactly match the same designs seem on the exterior, which prompts the question: what on earth are they? The space within is now filled with masonry, but they cannot simply be surface decoration, since that would not explain why the niches evidently go through the thickness of the wall.

Could they have been tomb niches, ready made and waiting for inhabitants, as Simon Jenkins suggests? Well, plainly not, I think: you wouldn't have an open archway through the outer wall of a church in this way. Could they have been slots in the wall for the interment of rich parishioners, in the manner of the rather bathetic niches one can see in modern crematoria, waiting for someone's dear departed to be sealed in with a marble plaque and some polyfilla? Perhaps so, but it's odd that none of them have anything suggesting that people are actually buried there.

Having mused at these things, I went up to examine the west end. This is now filled with a lot of heavy woodwork: a west gallery, and screens cordoning off a chapel in the south aisle and a vestry in the north. It's all rather good: the church is big enough to balance the solidity of it all, and the style is in a pleasant 1950s pastiche of Georgian work. The juxtaposition of Gothic and Classical can work very well, if done nicely, and it shows good judgment on the part of the people responsible in 1952 for the installation.

|

Passing under the gallery, and through a doorway in the blocked-up west wall, one enters the tower. This is rather disappointing: the parish now use it as a kitchen, and it's filled with rather a damp musty smell. The galilee, one door further to the west, is likewise disappointing, filled with clutter and a cubicle toilet in the south-east corner. I suppose it makes sense for the parish to make use of the south door and to convert these rooms into something useful (though what with the vestry at the end of the north aisle and the blocked-off north porch they'd already have more space than most parish churches); and it's only really a continuation of the much earlier modification of the galilee to include a parvise.

Still, it would be nice to enter Holy Trinity as originally intended, through the grand western entrances.

Mind you, there's something unintentionally shamanistic about the present set up. If you start at the west door and start walking back eastward, you pass through a series of increasingly small, dark spaces: the kitchen under the tower is not quite a longbarrow, but I'm firmly with Douglas Adams that there can be something of the soul-ordeal about tea urns. One passes through the old tower arch, and out under the western gallery, and the soul-journey is complete: suddenly there's a beautiful vista of the nave, with all the tall pillars stretching out in front of you.

You also get a good view of the medieval stone screen in the chancel arch. Bottisham doesn't have the only stone screen in the county - there's another one in Harlton, off to the south-west of Cambridge - but this is unusually lovely and is built of that fine grey stone, like cloud captured in solid form. The screen has three openings which are just about equal in shape in size (though they are slightly uneven and squiffy, which only adds to the charm). A beam runs across the top of the ensemble, and each archway is framed within a rectangle of thick tubular moulding, with quatrefoils in the spandrels of the inner two verticals. The side openings also have low dados composed of rails supported by four little arches on each side (Pevsner claims that this is a 19th century insertion).

If this weren't enough, on either side of it are the remains of some 14th century wooden screens forming enclosures in the eastern ends of the aisles. The woodwork is obviously original, but the screens seem to have been moved. Could it originally have been a second screen crossing the whole width of the church, or two parclose screens that have been mucked around with a bit? Whatever their origin, they're wonderful things. Around the base is quite a high dado panel, with remnants of original paintwork. Above that are openings, which are topped with the most extraordinary wooden tracery I've seen, full of complicated spiky patterns and interweaving arches and zig-zags. It's almost as though a piece of the Alhambra has found its way into sleepy Cambridgeshire. The fractal tracery supports a beam, which in turn supports another frieze of tracery, topped off with a line of crenellation.

Whatever the original purpose of the screens, they now enclose two groups of monuments bunched rather awkwardly together in the corners of the aisles. Each enclosure is lit by a large window in the north and south walls respectively. These look like rood windows, but they are in slightly the wrong place to have cast much extra light on the screen in the chancel arch: perhaps they were inserted when the aisles were refitted as guild chapels (that there was such a chapel on the south side, at least, is demonstrated by the trefoiled piscina and sedilia in the south wall there). The tracery is rather unusual: the windows are very elongated, with quite sparse tracery at the top and a transom across the middle. The lines of stonework are reproduced in free-standing tracery set a few inches in to the church, which is yet more evidence of unusual richness (the only place I can recall having seen something similar was in the east window of York Minster - rather an exalted comparison for a little place like Bottisham).

The north side contains inhabitants whose name is already familiar to me, for here are several members of the Allington family of Horseheath. On the north wall, behind some iron railings, there is an alabaster monument commemorating Thomas Pledger, who died in 1599 aged 69, and his wife Margaret, who died the previous year aged 778. Margaret was the daughter of William Conyngesby of King's Lynn, and previously was married to Sir Giles Allington of Horseheath. Since Conyngesby was one of the Justices of the Common Pleas at Westminster, and Giles was the most powerful nobleman in this part of the county, Margaret was a good catch for Thomas: his relative lack of distinction makes one wonder why such a powerful widow didn't acquire a more illustrious alliance. The effigies of the pair kneel at desks, surrounded by the usual confection of pillars and strapwork.

Next to them, under the east window, is a small monument to the infants Lionel and Dorothe Allington, who died in 1638. The tomb itself is a bit unpleasant: two cherubs hold back the folds of a tent, revealing two black marbles steps like fishmongers' slabs with the Allington children lying on them. The rhyme commemorating them is nice:

Stay Passengers and wonder whom these stones

Had learned to speake, infants Alingtons

These ye worlds strangers come not heere to dwell

They tasted, liked it not, and bad farewell.

Nature hath granted what they begd wth teares

As soon as they begun to end theire years.

Around these monuments is a collection of chunks of stonework (including some figures and a large Norman-looking consecration cross). There's also, on the south side, the remains of a chest tomb which must once have had a stone canopy over the top. That has now gone, and the brass that once lay in the marble slab has been ripped up, so it is now entirely anonymous.

There was another, even bigger brass, which lay in the central axis of the nave, close to the chancel arch. Like the tomb brass, it's now gone, but one can make out some details: there are Lombardic characters around the edge (which I couldn't read, alas) and the silhouettes remain of the inlaid forms. The figure was very large - certainly life-size - and was surrounded by an elaborate architectural canopy along with two censing angels. Yet more mysteries: I wonder who he was?

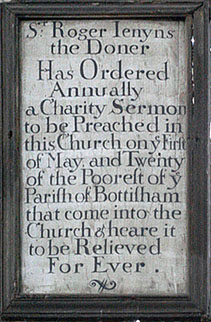

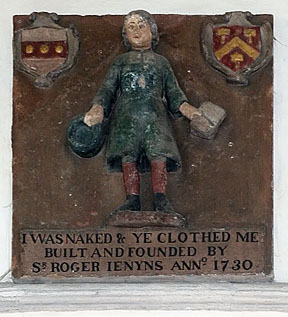

The southern chapel contains just one monument, to Sir Roger Jennyngs and his wife Elizabeth. Sir Roger, who died in 1740 aged 77, reclines urbanely on a pillow, complete with periwig. He holds the hand of Dame Elizabeth, who lies on a step below him. Dame Elizabeth died in 1728 at the age of 62, and her last request is commemorated in the inscription below: by her desire, Sir Roger endowed a school for villagers, along with enough money to ensure clothing for the schoolchildren. The old sign for the school survives and hangs high on the south wall: it depicts a boy holding hat and book, with two coats of arms on either side of him and an inscription saying 'I was naked and ye clothed me / Built and founded by Sir Roger Jennyngs anno 1730.'

After all this excitement, the chancel was a bit dull: it is well lit by big Perpendicular windows, but subsequent generations have scrubbed all the life out of it. I liked the modern choir stalls, with big stalks for candles, and the east end is nice. In the south wall, the 14th century masons reused the 13th century sedilia and piscina. There are three seats in the sedilia: the two westernmost containing arches with moulding over the top, and the eastern one having a completely plain round-headed arch. The piscina has square shouldered arches, with a small pillar dividing two basins in the middle. The whole ensemble is unframed, and painted in the same colour as the walls thereabout, so they seem to emerge rather abruptly from the masonry. I presume that the lovely east window, composed of a triad of lancets framed with granite shafts, also dates from the same time.

The church is (as of July 2018) open during daylight hours.