John Aubrey tells us '...and in the County of Cambridge, there is an Hamlet named Horse-Heathe, which name comes from 'Horsa-hythe'. This being because Horsa, brother to that most famous Saxon King Hengist, brought his shippes to shore here'

I jest, of course. Aubrey was a 17th century antiquarian, the author of Brief Lives and 'natural' and 'ancient' histories of various english counties, but not Cambridgeshire. The name 'Horseheath' is much more likely to be something to do with heaths and horses than ships and Saxons. Bet I had you going, though.

All Saints is kept locked, but there are several keyholders listed. I went first to the nearest, but the owner was out and so I got to have a conversation with her lovely big ginger cat - he wasn't able to give me the key, but he did show me his doorstep and asked what I was doing carrying a helmet with wings on it. In the end, Mark had to nip round the corner to find the key from somewhere else.

Whilst he was doing so I had a good look at the exterior. The nave is huge - it has no aisles, and the big Perpendicular windows stretch right up to the parapet. It quite dwarfs the small Decorated crossingtower, though that is quite elegant. Like several churches in this bit of Cambridgeshire, the staircase is inside the tower rather than in a turret - we found the tiny doorway after we got in. The porch provides a nice place to sit, but dates from the 1875 restoration.

Inside, the nave is an extraordinary space. It is very tall, and as wide as it is high: the huge windows fill it with light, and it is the single best example of the Perpendicular greenhouse ideal that I've seen so far in the county. It has a nice roof, too - a boss with '1951' carved into it indicates the most recent restoration, but most of it is medieval.

The font is reasonably nice - a Perpendicular octagonal model, with blank panelling on the stem and piping around the eight faces on the bowl. The faces themselves are completely blank - I wonder if they were intended for carvings? They're hardly big enough for the scenes of the Seven Sacraments one sees in Suffolk and Norfolk, but they could certainly have fitted a few saints' emblems on there. Without any decoration, it looks a bit incomplete - but maybe I've been spoiled by too much East Anglian luxury in those other counties.

More interesting is the rood screen: it looks suspiciously new from the west, but the eastern face is so corroded and ancient-looking that it must be original. The doorways for the rood stair are visible in the north-east corner of the nave - now blocked up, although the lower doorway is decorated with lovely carvings of flowers and a heart with vines growing out of it in the spandrels. The nave is so wide that the upper door is a long way from the chancel arch and the present location of the screen. I suspect that originally it ran along the whole of the west of the nave, from the stairway across the chancel arch and right to the south wall. If so, it must have been a spectacular thing - not just a very long screen, but a very high loft, given the height of the rood stair. The present screen is, I suspect, a fragment of that original screen, moved back to the chancel arch when the loft was taken down. Examining the woodwork around the edges of the screen where it meets the arch, the carving looks newer and cruder - so perhaps they modified it to make it fit better?

Up at the west end of the chancel, we found a pair of splendid tombs. The older one is on the southern side. It is in the form of a black marble slab, raised up on fat little columns, on top of which is an effigy of stout bearded man in armour with a dog at his feet. Underneath the slab lies a similar effigy, with some painted coats of arms on the back wall. These are a father and son, both called Gyles. The first (let's call him Gyles I - though there were many more before him) died in 1522 and his son Sir Gyles II was amazingly long-lived - he was born in 1500 and didn't die until 1586. Originally, there was have been a second tier on top - more columns and a canopy over the whole thing. Some fragments of the latter have been preserved and are displayed on the wall to the east.

The thing that really captured my imagination is that the family history of the Alingtons through no fewer than five generations is inscribed on the monument. First, of course, we have Sir Gyles I, who married Mary Spencer and had ten children. Then we have his eldest son and heir, Sir Gyles II, who had three wives over the course of his long life. The first was Ursula Drury, who bore him one son: Robert, his heir, who was himself to have ten children. His second wife Alice Myddleton had nine children before dying - and he finally settled down with Margaret Tallakarne, a widow who was presumably old (or sensible) enough not to attempt to extend the family even further.

Alas, Sir Gyles II's long life was possibly a mixed blessing. His eldest son Robert died in 1552, and his eldest son Gyles III died in 1573 having lived just long enough to father a son - so that in the end Gyles II was succeeded by his great-grandson - Gyles IV (son of Gyles, son of Robert, got that?). I won't even start to list the various siblings - Elizabeths, Janes, Richards, Beatrixes, Alices and Williams galore. I spent a good ten minutes trying to work out all the family connections - great fun, though I ended up feeling rather sorry for old Sir Gyles II, watching his descendents drop dead while he remained resolutely alive.

On the other wall is monument from a little later - on it lies Sir Gyles Allington IV who died in 1638. The two tombs demonstrate the changing fashion over the thirty-odd years that separate them: while the older tomb is all sober black marble and white effigies, this is commemorated by an alabaster extravaganza. Up on the wall two black pillars frame a space filled with elaborate strapwork decoration. Above, painted shields testify to Allington family pride. Below, full length effigies of Sir Gyles and his (first) wife Dorothy recline on a great chest tomb. Below them on the front of the tomb are images of their children, kneeling in a line - sons on the right, daughters on the left. The eldest son (another Gyles who died, along with his mother, in 1613) carries a skull, which suggests that the family habit of losing heirs continued into the 17th century. The inscription makes it clear that this tomb was erected on the death of Lady Dorothy in 1613, it also makes it clear why she required such a large monument..

|

Dorothy was an extremely well-connected woman. The Allingtons had produced two Speakers of the Commons in the 15th century and were evidently a family of some importance, but even so, Gyles IV's marriage to Dorothy Cecil placed him in the very middle of the political establishment, not just of Cambridgeshire, but of the kingdom. Dorothy's father was Thomas Cecil, 1st Earl of Exeter - eldest son of the great William Cecil, Elizabeth I's chief minister for forty years. William was succeeded as chief minister by his younger son Robert - who was the architect of the peaceful succession of the scottish King James in 1603. This continuing central role had made them one of the most powerful families in Britain. It was a remarkable coup to marry into such a dynasty - and suggests that the Alingtons must have been just about the foremost gentry family in Cambridgeshire at the time. [Mark adds: his high connections were no help when, once Dorothy Cecil died, Sir Gyles married Dorothy Dalton. She was not only rather less exalted a personage, but also his niece. In 1631 he was convicted of Incest by the court of Star Chamber and fined the extraordinary sum of £32,000. Two years later the offenders were pardoned "provided they shall not hereafter cohabit". None of this affected his son William (by the first Dorothy), who became the first Baron Alington of Killard in 1642.]

So excited was I by this heady mix of politics and genealogy that I didn't notice for a while that I was standing on a brass. It is a fine figure of a knight in armour with a dog at his feet. His name is William de Audley, and he died in 1365. Above his head survives a little brass angel diving out of a cloud, ready to bestow honours upon Sir William. It's a very rare survival.

These are all splendid monuments, in different ways - one gives us a window into the 14th century, another hints at the turbulent family life of a great local patriarch, and the third trumpets his great-grandson's connections with the great and the good on the national political scene.

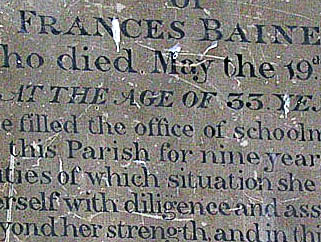

Fascinating as those are, though, the most moving monument is up at the other end of the church. A little wooden board on the west wall of the nave commemorates Frances Baines, who died in 1846 at the age of 33. The inscription reads:

She filled the office of schoolmistress in this parish for nine years, to the duties of which situation she devoted herself with diligence and assiduity beyond her strength, and in this cause having passed six months at an Infant School training Institution to qualify herself further as a teacher of the younger children more especially according to the most approved method. She suffered from the close application there required, and ultimately fell a sacrifice, to her praiseworthy exertions. In grateful recollection of benefits received, her sorrowing scholars have erected this monument.

All Saints is kept locked, but several keyholders are listed.