The church of the Assumption at Harlton is a rather unassuming building from the exterior. The 13th century tower is rather squat, and has been patched up over the years with stone in many colours [Mark adds: I could swear there are breeze blocks in the tower - something I've never seen anywhere else]. The west window is large but blocked, and there is no clerestory. The proportions seem all wrong, from the exterior: the aisles are exceedingly tall, and the whole building is inelegantly boxy.

The interior, though, is one of the most dramatic in Cambridgeshire. There is no clerestory, but none is needed. The nave arcades are so lofty that the aisles are as high as the nave roof, and light streams in from the side windows. This is very early Perpendicular (the tracery in the chancel windows suggested to the RCHM that this was built in the late 14th century, when Decorated forms were transforming into the later style). The piers themselves are quite elaborate (four octagonal half-shafts with panelling in the diagonals between them), but all the vertical lines are exaggerated. This isn’t a particularly big building – the nave is only of four bays – but it seems to soar.

This matter of the relationship between the inside and outside forms of a building is one that fascinates me, as it happens. One of the many essays I’m never going to get time to write is about the balance that different religions, or different traditions in the same religion, have struck between the interior and exterior of a building, and how that relates to the forms of the religion itself.

Consider the Parthenon, for example. The public religion was conducted outside the building, and it is the exterior that seems to have been made to be the most beautiful part, as well as the most richly decorated. True, the temenos within is where the Goddess dwelt, but its proportions are dictated by the need to produce a harmonious exterior.

|

This outward-looking building reflects an outward-looking, public, political religion. By contrast, early Christian churches are entirely inward looking: the building creates a sanctuary where the liturgy can be played out, and the exterior often takes the form necessary to produce that sacred space. I suppose one example might be the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople: the exterior is awkward and undecorated, but the interior space is sublime.

The Parthenon and the Hagia Sophia: such grand comparisons for a little parish church in Cambridgeshire! One of the things that struck me, though, was that Harlton church pushes much more towards the inwardness of the latter than the exterior form of the former.

Most of the surviving churches in western Christendom are balanced between the two extremes, and this is particularly true of the grand English churches. (I’d say that such compromise is characteristic of the Church of England, but that would be anachronistic, of course). Despite its pure Perpendicular lines and radiance, Harlton is in some respects a throwback to an earlier attitude, where an unlovely exterior was a worthy sacrifice for perfection within.

Not, I hasten to add, that Harlton is perfect. In particular, the original building has been badly treated by its custodians over the ages. The tower arch is filled in with a particularly bleak wall. The roof is 16th or 17th century, but it has lost the statues it once had on the corbels. The worst damage has been done to the screen – but I’ll mention that in a moment. Some interesting bits and bobs survive, though. The roof corbels are mostly intact. That they are carved in the forms of grinning angels isn’t unusual, but the fact that some of them are bearded certainly is. There are also some little leering faces on the drip-stops of the arcade.

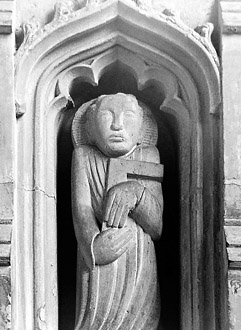

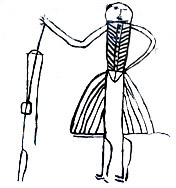

In the north aisle there is the doorway to the rood stair, which curves up behind the east end of the arcade. The door itself is rather a rare 14th century survival, with nice medieval ironwork on the hinges. Next to it, in a case against the east window, is a graffito of an Elizabethan figure. He has large puffy breeches and a high-necked jacket with buttons down the front, and he carries a spade. The label speculates that he might be a gravedigger. Until 1998 the stone on which he is carved was part of the west wall of the aisle, but it became detached: thankfully it was preserved.

|

The south aisle is rather grander than the north: the east window has a niche and bracket on the right hand side, and a little bracket on the left. It suggests that this was probably a guild chapel. To the right, there’s also a block of stone with a very ancient-looking angel carved onto it, carrying a scroll. It’s very defaced, and there’s no obvious place for it to have come from – I wonder what it was?

Against the south wall of the aisle is an extraordinary monument. It commemorates Henry Fryer, who died in 1631, along with his parents Thomas and Mary, and his stepmother Brigit. It follows a familiar pattern – painted alabaster, with the main figures kneeling in a central alcove surrounded by pillars, cherubs, architrave, cherubs, coats of arms and more cherubs – but is unusually full of character. Henry and his parents kneel in a line under the central arch: he wears splendid red, green and gold armour, and his parents are dressed in black. His stepmother reclines on her side on a chest in front of the arch, carrying a book. All four of them look extremely mournful: Henry in particular has a haunted expression that reminded us of the look that Charles I usually wore. On either side of the central arch, the pediment is supported by caryatids. The woman on the right looks merely sad, but the figure on the left (a bearded man) is weeping, and wipes his eye with the hem of his cloak. Below is a fine verse, commemorating Henry Fryer’s piety and charity:

‘Encloister’d in these piles of stone

The reliques of this Fryer rest,

Whose better part to heaven’s gone

The poor man’s barrels were his chest

And ‘mongst these three, grave, heaven, poor,

He shar’d his corpse, his soul, his store.’

In the chancel arch is a very rare thing: Harlton has one of the very few stone rood screens in the country. It is extremely solid looking. The dado is just a solid wall of clunch, though there’s a tiny squint on the left hand side that looks through to the high altar. The arches – an ogeed one over the doorway, and plainer cinquefoil lights on either side – are sturdy and powerful, and the stone beam across the top has little battlements: what a magnificent rood loft this must have supported! The loft is gone, of course, but removing the screen itself would have been a very difficult undertaking. Unfortunately, defacing it wasn’t: the central arch looks like it must have had some good carving on the front at one point, but that’s all gone now, and the screen does have a denuded, hacked-about look to it. Inspecting the back of the screen and arch suggested further enticing details of what was once there: we found a couple of pedestals which Mark thought might well have supported the statues of Mary and St John that would have accompanied the Rood, and the number of holes and remains of metal brackets in the chancel arch imply that there was once a big tympanum filling the space behind the statues.

The sedilia in the chancel suffered an even worse fate than the screen, since they have completely disappeared: below the easternmost window in the southern wall is a large blank space which must once have contained three seats, but is now rather raw and empty. I image it was rather like the set of sedilia that survive at Whittlesford or have been restored at Gamlingay. The piscina does survive, but is now used as storage for books (which is as good a use as any, I suppose).

The rest of the chancel has fared a bit better. The 16th century choir stalls are quite nice, and the east wall is unusually grand. The large Perpendicular window is framed by two big niches, with tall canopies decorated with crocketting and little fake vaults. The brackets sit on engaged columns that are decorated with blind panelling. Around the east end there are also various bits of stone that have been reset into the walls. At first, they looked like cabbages with scrolls wrapped around them, but I presume that they’re supposed to represent clouds.

Behind the altar is a set of statues of the apostles, made for the church in the 20s. They are in a primitive Romanesque style, and I liked them very much. They had the abstracted significance of chess-pieces, and I amused myself for a while by wondering what complex game, riven with omens, they might be resting from. That, though, starts to sound like bad theology, so I had better stop.

The Assumption was open when we visited