There are lots of interesting Norman churches in this southern part of Cambridgeshire - they seem to cluster around the floodplain of the Granta (one of the youthful incarnations of the Cam) on the main route down from Cambridge towards Saffron Walden. The valley has been a major thoroughfare for a long time, of course - just across the county border is the site of a great Roman fortress at Great Chesterford, and the even older Icknield way crosses here on its way up to Newmarket Heath. It's hardly surprising that there's such a concentration of rich Romanesque work in the area, at Thriplow and Pampisford and Duxford and Ickleton. My favourite is indubitably the wonderful redundant church of Duxford St John, but SS Mary and Andrew at Whittlesford is pretty special too.

The shape is instantly recognisable - a central Norman tower, surrounded by nave, aisles and chancel. The original plan of a tower separating a small nave and chancel is somewhat obscured by later building: in the 13th a large south aisle was added to the earlier nave, followed by the south chapel in the mid-14th century. A Perpendicular facelift later on added new windows. Still, hints of age abound. The groundplan is impossible to mistake, for example.

More excitingly, there is a little round-headed window in the south face of the tower that hints at an even more distant past. The round head is carved from what was originally a single lintel set into the wall, and this lintel is carved with the figure of a Sheela-Na-Gig.

The Sheela-Na-Gig is a female figure - usually a crone - squatting and pulling open her vulva. This is so obviously - shockingly - a pagan religious symbol that the presence of so many sheelas on Norman churches is surprising, to say the least (for an interesting website about Sheela-Na-Gigs in the UK, along with a distribution map, go and have a look at this excellent site). Were these old stones reused in later building projects, or was this a carving that post-dated the conversion? The latter would be an intriguing possibility: Christianity has always excelled at appropriate numinous images from other religions and absorbing them, from the Conquering Sun to Jesuit syncretism in Latin America. In this case, though, I'm sceptical: the Sheela-Na-Gig is so uncompromising a sexual image that I can't see how she could have transmuted into something acceptable.

So, my opinion is that the Whittlesford sheela is from a much older time - a stone that was reused when the church was built. The shape of the block also suggests so - it is somewhat irregular, and the round window-head does seem to have been cut into the carvings.

This sheela is unusual in that she is accompanied by a male figure dancing towards her from the right. The carving isn't particularly clear, and we didn't really pay much attention to it until we had read about it inside the church, but with a little inspection she is unmistakeable: even if the heads and faces have softened with time, erosion hasn't made the deep gash of her vagina any less provocative. [Mark adds: the dancing figure is a human-headed animal with a very large erection - the assymetric shape of the stone suggests that there may have been a matching animal on the other side of her too - clearly a popular woman... I'm not as sure as Ben that the stone - as opposed to the imagery - is pre-christian. I've seen sheela-na-gigs on several churches and they cannot all have been re-uses of already extant carvings. I wonder how many Whittlesford residents ever look up at this old old goddess displaying her power?]

The rest of the exterior is almost banal by comparison. The central tower has a Perpendicular upper stage, and a typical South Cambridgeshire spike. From the south, the tower and nave roof look rather swamped by the huge expanse of the aisle roof, which sweeps unbroken from the west face through to the east end of the side chapel. The entrance is through a lovely timber porch, built by Henry Cyprian, who also left money for a chantry in 1351. An inscription around the inside says 'Henricus Cipern me fecit', and the silvery beams overhead have little heads on them. It's worth savouring before entering the church itself, although do try not to fall over the rosebushes in the graveyard as Mark did, nearly breaking his neck in the process.

Inside, the south aisle continues to be dominant: the roofline reaches the wall a good way above the nave arcade, with the result that the nave shrinks by comparison. The whole church is a magnificent jumble of different bits of building and fittings. A big wooden chest bound with iron sits in the south aisle underneath a modern table complete with teacups and an urn. The nave is filled with fine ancient pews, very elaborately carved with blind arcading and little buttresses. I did wonder whether the wood might have been taken from a screen and reused, but there seems rather too much of it for that. One of the windows in the north wall has some Victorian glass portraying Henry Cyprian, shown carrying a model of the church (the image, incidentally, which we have on the front page of the website).

Most unusual of all (for Cambridgeshire, at least) are the fragments of a Nottingham alabaster reredos, now in a cabinet set into the north wall of the nave. Nottingham alabaster was once famous throughout Europe, but virtually all the examples in England were destroyed in the Reformation. These few fragments are rather nice, though: I especially liked the image of the Virgin.

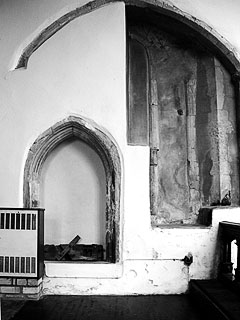

I like churches with central towers - the crossing is almost always an interesting space, and I like the way that it complicates the various views through the building. The crossing here doesn't result in quite the same Escher-like vistas as St John in Duxford (for example), but it's still intriguing. It has some remains of wall-painting above the eastern arch. The guidebook says that it is the remains of a doom, but I couldn't make out anything as elaborate as that, just a shield, a pomegranate and lots of flowers. There is also a bit of medieval graffiti on the north side of the western tower arch, depicting an archer with a longbow. The remains of the rood stair sit at the eastern side, which means that the screen was behind the crossing rather than in front, unless there were two.

As I said earlier, the chancel is probably mostly a Norman structure too. Any outward signs of that are long disappeared, as the different centuries have laid their hands on the building. The result is a bit of a puzzle, with all the different ages rather jumbled up. So, we have a three-light Perpendicular window in the north wall that has lost its rightmost light. When did this happen? There is a big Victorian wall-plate of a particularly overpowering Gothick design hanging just to the right, but I was unsatisfied, because the wall blocking in the window seemed older to me. To the east of that, there is an archway fossilised into the primrose-coloured plaster. The new plastered wall within the arch is not parallel with it, so that on the right hand side the back of a recess is revealed, decorated with smaller arches. On the left, where the larger archway is most deeply buried, is a blocked doorway lower down, about 4 ½ feet high, that goes to nowhere. Further east, yet another blocked up arch contained an impressive corn dolly when we visited.

Architectural palimpsests like this are puzzles in four dimensions: the building in space, and the building in time. The puzzle consists in inferring as much as possible about the latter from examination of the former. I found this wall in Whittlesford very difficult to read, but here's a possible story: There must have been a chapel on the north side of the chancel, accessed through the arch. Frequently, in the wall between such an arch and the altar, there would be a tomb: the place of honour for a wealthy benefactor. (The obvious suggestion is made by the guidebook that this could have been Henry Cyprian's chantry chapel - it seems very possible, but there's nothing more than circumstantial evidence). Hence the larger archway, with the smaller archways higher up in the wall to the right. At the time, I remember wondering if those smaller archways were always blind, or whether perhaps they had once been open and had acted as a sort of screen for the chapel beyond. Both would be very unusual decoration in a parish church. If I'm right about this having been a tomb recess, the doorway on the left would have been the entrance to the chapel. This leaves several questions unanswered (who was the tomb for? why and when did the chapel fall? what is the second doorway for?), but it seems to me the most likely hypothesis - I'll keep searching for more information, though, and update this entry if I turn out to be wrong.

The rest of the chancel is a little easier to understand. The eastern wall has what looks like Jacobean wood panelling behind the altar. On the south wall is a particularly elegant Perpendicular window, with the line of the mullions continuing down to form a set of three sedilia with nice blind arcading at the back. Just to the west is the priest's door, which sits rather awkwardly at the junction of walls between the chancel and the south chapel.

The south chapel itself is separated from the chancel by two big Perpendicular arches, and it has a parclose screen. Neither Pevsner nor the church guide mentions this, which I find odd: the tracery seems to have been renewed, but I thought that the top beam was medieval. It's very nicely carved, with a little man's head and a lion, amongst other things. In the east wall of the chapel, next to another lovely Perpendicular window, there is a shallow niche with remnants of paint: they are now turquoise and red and black, but that probably represents the decay of the pigments rather than the original colour scheme. There must originally have been a bracket below the niche if it was to hold a statue. The chapel was built by the guild of St John the Baptist, whose guildhouse survives in the village.

So many questions remain for me about this church, and I think we need a return visit so that I can reflect a bit and try to unpick more of the historical puzzle. I did come away, though, feeling that SS Mary and Andrew was one of the most exciting churches I'd visited in the county. There's no single feature that stands out as supremely magnificent, but it provides a lot of food for the imagination.

SS Mary and Andrew was open when we visited