What happens when your parish is exceedingly wealthy in the 15th century? You end up with the grandest church in Cambridgeshire, that's what. St Mary is a great gorgeous Perpendicular giant of a building. I suppose it invites a comparison with the great wool churches of Suffolk, and St Mary is indeed just about the only church in this county (college chapels in Cambridge aside) that can stand up to, say, Lavenham. It's easy, though, to fall into the trap of referring to an 'East Anglian Perpendicular style', of which the Suffolk and Norfolk glasshouses are the epitomes.

This is unfair, though. A lot of Cambridgeshire's churches do look outside the county for their inspiration, and towards Suffolk especially, but there is a distinctive Cambridgeshire style in many places: elusive but definite. One of the nice things about Burwell is that we can find in St Mary several of the elements that make up this style.

Take the tower, for example. The octagonal lantern dates from the 15th century rebuilding of the church, and is the sort of thing one sees quite a lot in Cambridgeshire. Another very fine one can be seen over at Sutton, for example, or at SS Cyriac and Julitta in Swaffham Prior. Many (though not all) of these octagonal towers seem to be influenced by the most famous octagon of all, Alan of Walsingham's wondrous crossing at Ely Cathedral.

Another particularly Cambridgeshire feature is the polygonal stair turret in the south-west corner. It is a long octagonal shaft, with a little battlemented top - exactly the same as one sees at Haslingfield, or Great St Mary's in Cambridge, but never in Suffolk. The difference is, I suppose, that they could afford to build in stone here. There's not much stone in Cambridgeshire, but there are some good waterways - indeed, Burwell's prosperity came from its position as a well-placed inland port. In such places, there was both the money and the ability to bring stone in from Barnack over on the other edge of the fens, and this is what they did.

The tower also demonstrates that Burwell's prosperity did not arise just in the 15th century. The base is Norman, as the blocked-in windows on the north face bear testimony - useful architectural fossils. The tower is big, especially given its age, so Burwell had been rich for a long time before the great rebuilding.

The size of the tower suggests, I suppose, that the old St Mary must have been an impressive place. There are no signs of it now, though, because apart from a couple of bits of 14th century work at the west end, the body is entirely 15th century. The grand rebuilding probably happened while one John Heigham was vicar, between 1439 and 1466. His shield with three nags heads can be seen in the chancel. Don't hurry inside without admiring the wodewoses on the porch, though.

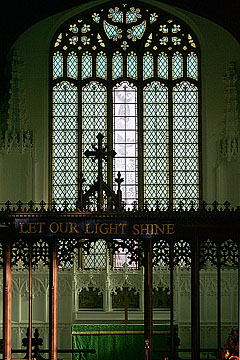

The interior is every bit as impressive as one would imagine. The stone carving is crisp and elaborate - from the lozenge-shaped piers engaged shafts rise to the roof, dividing the clerestory into panels containing blind panelling and the vast windows of the clerestory. The most elaborate decoration of all is above the chancel arch: a rose window is surrounded by a profusion of panelling, shields and niches.

It's very impressive, but I found, rather to my surprise, that I didn't like it very much. I say 'to my surprise', because I'm normally a great fan of Perpendicular architecture - I love the feeling of space and light it produces, and the sharp lines of the windows, when they're done well. Here, though, it just doesn't work for me. The same thing happens at Lavenham in Suffolk: both churches cross the line from being grand into being ponderous. The lines here at Burwell are crisp and strong, but they don't soar, and the elaborate decoration is a bit oppressive. Perhaps this is what Pevsner means when he says that the church has 'no mystery'.

In all fairness, I should say that this is the impression I got on our second visit: I was much more impressed the first time round. Maybe if I see the church with sunlight streaming through the windows I will change my mind again. It doesn't help, though, that the glass in the clerestory and chancel is green, which filled the church with a glutinous submarine light. Regular readers will be aware of my strong feelings about coloured glass, but I think that even someone who didn't share my prejudices would have to agree that St Mary would be much improved by having it all knocked out and replaced by clear glazing. [Mark adds: green glass is, of course, grim glass - if only we had the original crop this church once supported - alas Dowsing was here on January 3rd 1643 and he and his friends "brake downe a great many superstitious pictures"..]

One thing that cannot be said about Burwell is that it isn't impressive. Both Pevsner and the RHCM speculate that the mason here might well have been Reginald Ely, fresh from his work on King's College Chapel where he was the first of the four great master masons. It certainly bears some of his hallmarks, in the decoration of the nave arcades and decoration of the walls.

The guidebook also says that the window tracery bears a striking resemblance to that at King's, though I don't recall such a similarity striking me particularly. Here, though, is another of those Cambridgeshire themes. Particularly in the 14th, 15th and 16th century one would often find very prestigious building projects going on at one of the great establishments - Ely Cathedral, Ramsey Abbey or one of the big royal foundations at the University. Masons hired to work on these would often end up working on churches in the area - as John Wastell did at Great St Mary's and Soham, and Ely did here.

Before you go through to the chancel do have a peek in the north aisle. There's a painting of St Christopher by the north door (indicating that the usual entry used to be by the south porch, I suppose). He's a bit indistinct and his face has gone, but his club was very impressive. Next door there is a Jacobean wall monument in painted alabaster, with painted strapwork and all the works. It commemorates one Thomas Gerard and his wife, who died in 1613 and 1608 respectively. Have a brief look, too, at the screen - the top is completely restored, but the base is 15th century. And so, through into the grand chancel. So long as one can ignore the dreadful green glass again, this is exceedingly beautiful. In between the windows there are canopied niches - great elaborate ones, with complicated little vaulting and little pinnacles. They are supported by angels, although the faces don't look very medieval to me and I suspect they were recut by the Victorians. Still, the alternation of the windows with the niches is very effective, and the tops of the canopies turn into the shafts that run up the wall to support the roof.

As the guidebook says, 'The masons' work is impressive, but the fame of Burwell arises from the work of the medieval carpenters'. All the rooves are quite stunning. The chancel is particularly good - the height of the corbels alternates between high (above the windows) and low (above the niches) - the former are carved as stone angels carrying musical instruments, while the latter have wooden figures of saints, angels and kings. The roof is an arch brace, so there are no hosts of hammerbeam angels in flight as at Willingham and March, but the figures are still lovely. There are more angels in the aisles. Not content with their angels, the carpenters also decorated the wall-plates with a positive menagerie of beasts, birds and more angels. There are bears, and elephants, and foxes, as well as little images of the Annunciation and the emblems of the evangelists. In the chancel there is a monkey with a urine flask - a satire upon the medical profession. My favourites were a pair of tigers with a mirror, on the north side of the nave. According to the medieval bestiaries, this was the way to catch a tiger's cubs - here is a translation from the Aberdeen Bestiary:

When [the thief] sees the tigress drawing close, he throws down a glass sphere. The tigress is deceived by her own image in the glass and thinks it is her stolen cub. She abandons the chase, eager to gather up her young. Delayed by the illusion, she tries once again with all her might to overtake the rider and, urged on by her anger, quickly threatens the fleeing man. Again he holds up her pursuit by throwing down a sphere. The memory of the trick does not banish the mother's devotion. She turns over the empty likeness and settles down as if she were about to suckle her cub. And thus, trapped by the intensity of her sense of duty, she loses both her revenge and her child.

[Translation & Transcription Copyright 1995 © Colin McLaren & Aberdeen University Library.]

Before you leave, go and have a look at the brass on the north wall of the chancel. It commemorates Laurence de Wardeboys, the last abbot of Ramsey. Unlike some in his position, he resigned his abbey without fuss when the commissioners arrived in 1539. In return he was given an annual pension of £266. 13s. 4d, though since he died in 1542 he didn't have much time to enjoy it. Interestingly, his brass is double sided - on the back is a slightly earlier figure in full abbatial vestments. There is a convincing case that this was Wardeboys' first image, presumably made before 1539 - why else is there an indentation above his head in the shape of a mitre? Even demoted from Abbot to priest, he is a striking figure, and it's probably the grandest brass in the county. Unusually, his canopy still survives, as does a representation of the Resurrection above the figure.

In a sense he is the last image of a tradition that has a profound influence on most of the churches I've written about. This is a land filled with powerful priests and great monasteries. The greatest of all was, of course, Ely: for centuries the Isle of Ely was practically a private domain of the Abbot (and later the Bishop) of Ely, as they had secular jurisdiction over the territory. Ramsey too was a powerful place, and the Abbot of Ramsey could be a formidable political force. The influence of the great fen monasteries permeates Cambridgeshire and the Isle, and it has shaped almost all of the churches in the area to some extent.

Before you leave Burwell, stand in the churchyard and look the north-east. Until the mid-18th century, a second church (dedicated to St Andrew) stood across the road from the churchyard gate. We know that it probably had a round tower, and was owned by Fordham Abbey, but that's about it. The parishes were amalgamated in 1646, and by 1742 St Andrew was ruined, so only a few drawings survive.

St Mary is always open when we visit.