Stuntney - the name means 'Steep Island' - sits on a little hill just to the south-east of Ely, and would once have been surrounded by the fens like its great neighbour. Like most of the little island settlements in this area, it was firmly under the control of the great abbey.

In 995 it was bequeathed - with a chapel and a fishery - to one Wulstan of Dedham by a widow named Aescwen. Wulstan then gave it to Ely, and it functioned thereafter as a satellite: services were taken by a monk at the monastery, and then after the Reformation by a canon of the cathedral.

Nothing really remains from that very early period. Indeed, almost nothing remains from its Norman successor, save for three archways that were preserved when the church was rebuilt in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The basic form of the building is the same, however: a simple structure with a small nave and chancel. The later restorations gave it a glossy black flint surface, and a peculiar Italianate tower at the east end of the south aisle, complete with a pitched roof and a tinny little peal of bells.

One enters through a doorway at the west end of the south wall - one of the original Norman arches, incidentally, with nice zig-zag moulding on the arch. Inside, one is immediately struck by something unique: the internal structure is all wooden.

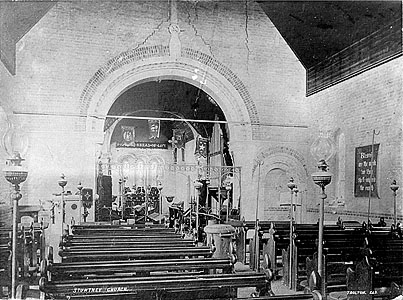

|

There is only one aisle, on the south side, and the arcade is composed of wooden piers: square shafts, each with four rounded engaged shafts that support steep arches in the arcade itself and over the aisle and nave. These then support the roof itself. The effect is very interesting, especially since it's all stained an odd dark green colour: it feels like a pastiche of Scandinavia, or a set from Noggin the Nog.

This dates from the 1903 restoration, when they had to rebuild much of the nave after finding that the 1876 structure was unsafe. They kept some of the Victorian windows, though, and also the Norman arches. The second and third can be found at the east end of the south aisle and in the south wall of the chancel, now blocked up with a war memorial and the organ respectively.

One feature saved from the original church is the font, which sits at the west end. It's a cheery squat scalloped thing: probably 12th century, though Pevsner thought that it was recut in the 18th century. It has a 17th century cover with four nice scroll handles swirling up to support a cross composed of turned rods: the carpenter who made this clearly specialised in newel rods.

The chancel arch is framed by some of the same wooden structure as fills the nave, but there is also a low rood beam set behind it within the chancel itself. It is rather massive, and supported on heavy brackets on either side. On top of it sits a rood group in much lighter wood.

For the most part, the chancel is uninteresting: it is all a bit dark and gloomy. It does contain some lucky survivals, though: a collection of worm-eaten wooden spires rescued from Ely Cathedral when the choir stalls were rebuilt in the 19th century. These things - I assume they were decorative shafts between the seats - were brought here, and stand around the edges of the chancel looking a little incongruous. They are fine bits of carving, though - elaborately carved leaves and spirelets and everything.

And that's it: not much more to say about Stuntney, save that it has one of the best views I've seen of Ely Cathedral. The hill at the west end of Holy Cross is not really as steep as the name of the village suggests, but it's a fine thing to sweep down on a summer's day, contemplating the gorgeous great ship of the Fens ahead of you.

Holy Cross is kept locked, but there are keyholders listed.

|

|||