St Andrew is not a large church, but it does manage to be quite imposing. It sits at the top of a steep slope above the road, which helps, but the effect is also given by some particularly noble architectural details.

The tower is built of stone rather than the more usual fieldstones or flint, and the bell-stage is decorated with the remains of blind arcading and some dog-tooth carving on the west face. It's battered and bruised (the arcading is lost on the north side, and in various places the masonry is patched up by brick) but it's still nice.

The chancel is also grand - it was rebuilt after a bequest by the Rector Richard Anlaby at the end of the 14th century in fine Perpendicular style: the side walls have great tall windows, and the new building is so big that it somewhat overpowers the more modestly sized nave.

Inside, the nave is small and neat, and has an old but rather utilitarian A-frame roof. The tower arch is wide, and slopes outwards. The stonework is all in very soft clunch: even the internal piers appear to be crumbling. Unusually, this stone is local - clunch was, apparently, quarried in Orwell during the Middle Ages.

The nave rebuilt in the 14th century, and isn't exceptional or exciting. I quite liked the heads at the bottom of the moulding on the south arcade, which were cheery and full of character, but other than that, the nave left me a bit cold.

There are more interesting things in the aisles, though. The north aisle was rebuilt in brick in the 19th century, but there are some old benches there with very plain gnarled poppyheads. The south aisle is original, and at its east end is a niche containing the remains of a fine 14th century sculpture of the Crucifixion. The figure of the Virgin has disappeared, but St John and Christ remain. It's very good: Christ in particular is very affecting, slumping in agony on a rough tree-trunk cross. It's also very rare, of course: nice to see it in a church, rather than in a dusty cabinet in the bowels of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The chancel is as light and airy as one would expect from the exterior. Unusually, though, the carpentry dominates the architecture here. The choir stalls are old and beautiful - no misericords, alas, but the woodwork is fine nevertheless. Even more dramatic is the barrel roof, which was reconstructed in the 18th century but appears still to be basically as it was when rebuilt at the end of the 14th century. It incorporates a great many bosses from the original roof, and is quite splendid.

There are the predictable shields honouring Anlaby's patron Sir Simon Burley, lord of the manor here and tutor to Richard II, who had been executed in 1388. Burley had fallen victim to the politics of the court, but his posthumous star rose once again in 1398 when the Duke of Gloucester and the Earl of Arundel, members of an opposing faction, were executed and Burley's estates released to his heir.

The roof seems to have been in part a celebration of that - hence the heraldic shields. (They have, incidentally, been repainted, and the Victorians inserted various coats of arms that are anachronistic with the original design, such as those of Trinity College). The most splendid bosses on the apex depict the heads and torsos of female figures, who look like they were once carrying tools. Their gilding is a bit shabby, but they are very grand.

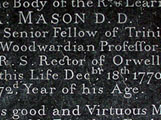

To the south of the altar is a wall-memorial for Jeremiah Radcliffe, one of the translators of the King James Bible, who died in 1611. He was a Doctor of Theology at Trinity College, and his bust is shown praying in front of a stone block, wearing the rich red doctoral gown. In front of the altar, another Trinity man is commemorated - a floor slab bears the name of Charles Mason, DD, who died in 1770 after many years as Rector and as 'Woodwardian Profeffor of Foffils' at the university, which made me giggle: I just hope he didn't have a lisp…

St Andrew was open when we visited