I love the borderlands between Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. For the most part, any interesting landscape is on the Suffolk side, but there are places where the high land is on the western side of the border, and we end up with pockets of woodland and gentle hills. Kirtling sits firmly in this territory, and the church has one of the finest spots in the parish. It sits next to the moat of Kirtling Tower, once the large Tudor mansion of the North family (of whom, more anon). Nothing of the original survives now except for the gatehouse, hence the present name for the building, but for the most part the parkland still survives. The richness of the living is indicated by the lovely rectory which also sits next to the churchyard; it is an Elizabethan building, though updated with a later brick frontage, and has a beautiful line of pleached limes in an avenue next to the low brick wall of the churchyard. It is all marvellously bucolic.

The church itself is pretty, though it presents quite a modest exterior. There is a tower after the Suffolk fashion, built of flints and possessed of cross-buttresses. The staircase is hidden within the southwest corner, which projects outwards a little way to accommodate it. This makes the west face slightly convex (the same thing can be seen in one or two other places, such as Barton). The tower itself has no battlements, but the rest of the church is decorated with them along the clerestory and the aisles. There are two porches: a plain north porch, and a rather nice south porch. A big Tudor brick chapel in the north-east corner piques the appetite for what lies within, and the whole thing looks rather typically Perpendicular.

For the most part, the church is indeed Perpendicular, but there are some fragments that have been incorporated from previous buildings. Within the church, I found a very deep lancet at the west end of the nave, and there is an old-looking blocked-up window in the north aisle. The most dramatic survival is the south door. Not only is there a wonderful round-headed Norman doorway, complete with chevrons and zig-zags on the arches, but there is a Norman door. It has been rehung, so the ancient iron straps no longer connect to the hinges, but it's still remarkable to see a door of this age (predictably, doors get a bit more battered than most parts of a church, so they don't tend to survive this long). Above the door in the tympanum is a intense and primitive Norman sculpture of Christ in Majesty, sitting on a rainbow. A lot of people have passed under that inscrutable, archaic face.

Inside, the intensity is replaced by Perpendicular urbanity. This is not, though, a run-of-the-mill interior. The nave arcades are all quite low, and do not match; on the north side the piers are octagonal, with rounded half-shafts on four of the faces, while on the south side the arches are surprisingly broad and rounded, with shields on the keystones. The southern piers are all very plain and round, and Pesvner thinks that they may be a survival of an earlier aisle originally knocked through the south wall of the Norman nave. Above these arcades, the clerestory is unusually tall, with grand Perpendicular windows soaring up to a high roof. The proportions are therefore unusual, and I thought the effect was very interesting: the space in the nave feels top-heavy, with the light above pressing the seating and arcades downwards into a rather constricted space.

Up at the east end of the north arcade, a grand archway leads through into a north transept chapel, which is also connected to the aisle by a half-arch in the shape of a flying buttress. This is a very interesting structure. On first sight, it appears to be a familiar 15th century guild chapel, complete with high roof and big Perpendicular window in the north wall. The east wall tells a slightly different story, however: there is a blind arch, within which are two smaller lancets. Was this another Perpendicular window that was, for some reason, filled in and replaced with the two lancets, or does this show that there was an older chapel in the same place that was merely spruced up?

The details in the chapel are particularly nice. On either side of the east window are sets of double niches - endearingly, they aren't on the same level, though they look to be roughly of the same age. The southern ones are smaller, higher up, and slightly plainer, with very slender ogees rising above the niches. Around them, there is some very sketchy blind arcading on the walls, and below them is a piscina. The northern niches are set within more elaborate panelling, complete with quatrefoils and criss-crossing arcading; and the niches themselves are big solid cinquefoil arches, with an octagonal pillar separating the two and remains of black and gold paint hinting at rich decoration, once upon a time. I also liked the roof, which is supported by some nice angels: no wings, but cheerful naïve faces and unusual hairdos.

Moving through into the chancel, there are some more remains of medieval paintwork. On the north wall are some paintings of swirls and leaves, and there is a little bit of colour left on another elaborate niche just to the north of the east window. Also in the north wall are the remains of two arches, which were probably windows at one point (though I did toy with the notion that they might have led through to another chapel, which might explain the odd configuration in the east wall of the north transept chapel). One of the arches is now filled with a Victorian Gothick monument to one John Crighton Stuart, Marquess of Bute, who died in 1848. Hanging nearby in a wooden frame is a brass which depicts a man kneeling and looking pious. The inscription tells a fascinating tale:

Here resteth the corse of Edward Myrfin, Gentleman, born in ye city of London, educated in good virtue and learning, travelled through all the countries and notable cities, princes' courts and other famose places of Europe and likewise of ye Isles of Greece and so to the Turkis court. Then being in the city of Haleppo on the borders between Armenia and Syria and so returning through Jewry to Jerusalem and so to Damasco, and from thence passing by divers countries with sundry adventures, arrived at length in his own nativity city, where shortly he ended his life in the year of our lord 1553 and in the 27th year of his age.

Myrfin was a merchant, and so his journey may have been a commercial one; but I do still wonder whether this wasn't a precursor to the Grand Tour. If only he had left us a journal…

To the south of the chancel, two big arches lead through into the grand brick chapel that I saw from outside. This was built in about 1500, but was subsequently taken over by the North family, and filled with their monuments. The first North to live at Kirtling was Edward North. He was born in London in 1496, the son of a haberdasher, but rose to have a stellar career. He was a successful lawyer, and attracted the patronage first of Thomas Cromwell, then of King Henry VIII himself. He was knighted in 1541, and joined the royal service first as Treasurer, then as Chancellor of the Court of Augmentations. This was the court responsible, amongst other things, for the distribution of the land and property seized by the crown during the dissolution of the monasteries, and - predictably - North made a huge amount of money out of it. In addition to buying Kirtling in 1533, he owned the old Charterhouse in London. On one occasion he was suspected of financial double-dealings, but was able to clear himself (though he did end up having to give quite a substantial gift of land to the king).

The apogee of North's power came towards the end of Henry's reign, when he became a member of the privy council. Under Edward VI, his star started to wane a little, and he was dismissed from his office and from the council by the Protector Somerset. In 1553 he was one of the prominent supporters of Lady Jane Grey, the ill-fortuned protestant successor to Edward, and although he was pardoned by Queen Mary (and even given a baronetcy) he never returned to the centre of political life, either under her or Elizabeth I.

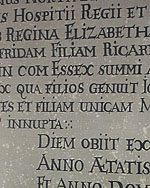

Edward North died in 1564, and buried in Kirtling. His monument is the northmost one in the chapel: a sober chest of black stone. At first, it looks rather unassuming, but the quality of carving is superb: it is thought that it came from the same workshop as that of Lord Treasurer Audley, who is buried with a similar tomb in Saffron Walden. The stone is very high quality - it is extremely hard, and the carving has remained deep and crisp. Behind it, on the east wall, is a plate with the following epitaph:

'Nature richly endowed Edward North, royal favour added great wealth, he held high offices thoughtfully and wisely, but even in great office he was unassuming; the gifts of nature increased by the favour of the ruler were all removed by dark Death in a single day. He died on the last day of December in the year of our lord 1564. He had the sons Roger, Lord North, and Thomas, and the daughters Christiana and Maria, of whom one is married to William, Earl of Worcester, and one to Henry, Lord Scrope.'

Edward North's wife was one Alice Myrfin, née Squire. She was the daughter

of a minor Hampshire gentleman, and the widow of one Edward Murfyn. She

married North in 1528; so, I wonder whether the Edward Myrfin commemorated

in the chancel was her son by that marriage?

Roger, the second Lord North, is commemorated next to his father. He

followed his father into politics, but was content to start on a local

level. He represented Cambridgeshire in the 1555, 1559 and 1563

parliaments, and after his father's death in 1564 threw himself into local

administration. He was the most powerful man in the county - the only

resident peer - and was both Lord Lieutenant from 1569, and Custos

Rotulorum from 1573, effectively acting as the chairman of the county's

bench of JPs. Over time, however, he gradually regained some of the

national political influence that his father had lost. He was good friends

with Elizabeth I: she sent him on several delicate diplomatic missions, and

visited him frequently in Kirtling, often to his very great expense. (It is

recorded that one visit cost him over £700 - a phenomenal sum). He married

Winifred, daughter of Henry VIII's Lord Chancellor Richard Rich, thereby

linking himself to a very influential family; and six years before the end

of his life he was made a privy councillor.

He died in 1600, and his monument sits next to his father's. Whereas Edward North's tomb is a masterpiece of sober understatement, Lord Roger's is extraordinarily garish: a wonderful riot of garish Renaissance detailing. Lord Roger himself lies in effigy, dressed in armour with his head resting on a helmet. At his feet sits a splendidly fierce gorged griffon: much better than the insipid dogs that often lie in such places, but I suppose that it takes an exceedingly rich man to have a pet griffon rather than the more usual greyhounds or bulldogs. He lies on a chest covered in swirling leaves and strapwork, to which there still cling some fragments of paint and so on. (It's interesting to compare this tomb with those at Isleham, incidentally, where rich American descendents of the Peyton family have paid for the tombs to be repainted in glossy bright emulsions: evidently there are no Norths amongst the wealthy New England captains of industry).

Surrounding this chest are six outlandish pillars, bulging slightly in the middle and covered in dense carving of foliage and things: vines on the westernmost pair, oaks in the middle and strawberry leaves, pomegranates and roses on the north-east and south-east respectively. These support a heavy canopy: Lord Roger's effigy is surmounted by a relatively restrained coffer painted in black and gold and white, but around the edges there is an architrave full of faces and more swirls, and the whole thing is surmounted by a huge three dimensional pile of strapwork, coats of arms, griffins, natives, women and cherubs. I love it - it's one of the most gloriously silly things I've ever seen.

All Saints was open when we visited.