‘We’re not in Kansas any more, Toto.’

Well, nearly, anyway. It felt like we had arrived at an intersection of various boundaries, in time and in space. It’s what the anthropologists might call ‘liminal’, I suppose; though to me the word contains disruptive echoes of ‘lymph’ and ‘limning’ and ‘luminal’. There is something of those latter two here, I suppose; certainly when we visited the air was full of cool November light, and the evening rays embellished the pale grey stone with gold; but the allusions definitely cease at ‘lymph’.

Yes, lots of limina – boundaries and thresholds. Kennett is in the place where the plains of Cambridgeshire are giving way to the higher, hiller land of the west. It also sits on a human boundary: this is right on the western border of the county, and is almost continuous with the Suffolk village of Kentford, on the other side of the thunderous A14.

The landscape makes it feel like Suffolk, too: the churchyard is reached by a track running around the edge of a small wood; rather a rarity in this county with the least woodland in all the country. The wood is a pleasant little one, running down to a small pond and covering small humps and holes which suggested to me that there were once clay pits here. While Mark was fetching the key, I went to explore the wood, disturbing some rabbits and imagining what an excellent place it would be for a child to play in.

Through the wood, the churchyard is enclosed with a low wall, and looks out over open fields to the east, towards the River Kennett. Kennett, incidentally, is one of the very oldest of place-names in England; it is shared with the River Kennet in Wiltshire, and the great Kennet longbarrows. One possible etymology sees it derived from the same ancient roots as the word ‘cunt’, which is a threshold of a sort, I suppose. Moreover, In Old Germanic, the word was ‘Kunton’, and comes ultimately from the Indo-European root ‘gen’ or ‘gon’, meaning ‘create’ or ‘become’: linguistic thresholds.

We visited in the middle of November (seasonal limen) around Sunset (diurnal limen), and found the churchyard wonderfully evocative. Almost as soon as I entered, my clumsy footsteps disturbed a cock-pheasant, and sent throbbing awkwardly through the air. It had been hiding in the long grass at the base of a monument so covered in ivy that it looked like Cousin It. Nearby, there were also some unusual wrought-iron memorials, as well as more familiar stone ones containing dying flowers and even some faded photographs.

Beyond the east end of the church is a great mallow bush, which – despite the late season – was still flowering profusely. Perhaps this is a sign of that more ominous threshold, global warming. At least Kennett isn’t in any danger of flooding, unlike the lower land stretching away to the north and the west.

So, what is it like, this church that sits on so many boundaries? Rather unprepossessing, alas, but the real world has a great talent for bathos. The exterior is all of pale rubble filled in with light grey mortar, and is modestly proportioned. The tower has fine cross-buttresses, and is a little narrow for its height, which gives a slight illusion of size. It also has some slightly off-centre bell-openings at the top, which are quite endearing. Indeed, the whole building has a slightly squiffy look to it.

The slate roof has grown a wonderful lot of moss, which is probably no good for the building but makes it all a lovely colour. Below it, the walls contain an intriguing collection of windows, all of different periods and sizes. The oldest appear to be Early English – there are some lancets in the south wall of the chancel, and a set of triple lancets on the east wall. From the outside, they looked like Victorian replacements to me, but the interior hinted that they might be older. Rather newer are the big trefoil windows in the nave – complete with flattened quatrefoils in the tracery about them - and the Tudor rood light.

Entry to the church is through the north porch, and a restored round-headed doorway. The arch above looks recut, and the pairs of engaged shafts on either side do too, down to about half their height; but the bases look old, and it suggests that there might be a Norman core to the church. The great thickness of the walls – shown by how deeply cut the older windows appear from inside – suggest the same thing.

The interior is mostly dominated by the Perpendicular north aisle, the arcade of which dominates the little nave. Much more appropriate is the little off-centre tower arch. It is a pleasant little church, but there’s not much to say – most historical curiosities were wiped away by the Victorians, and the furniture they left (an eagle lectern, a little chancel screen) isn’t especially interesting. In the chancel, a few interesting hints remain.

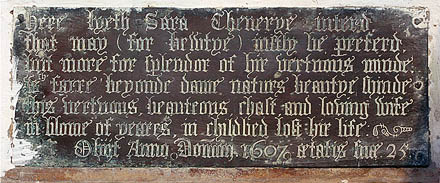

There is a little double piscina by the high altar has a very heavy Victorian pendant, carved with lots of berries and leaves in exuberant style. Below it there is a small brass plaque. It’s very easy to miss, since it is hidden away at floor level, but it’s worth a read.

The small rhyme commemorates Sara Chenerye, who died in 1607 at the age of 25, during childbirth. Two more limina, I thought: the mightiest of all.

[mark adds: here lyeth Sara Chenerye interd, that may (for bewtye) iustly be preferd, but more for splendor of hir vertuous minde, so faire beyonde dame naturs beautye shinde this vertuous, beauteous, chast, and loving wife in blome of yeares, in childbed lost hir life. Obiit Anno Domini 1607 aetatis sua 25.]

St Nicholas is kept locked, but keyholders are listed.