St Mary is one of the first rural Cambridgeshire churches I ever visited. Back at some point in early 2002 I woke up with a bit of a hangover, and decided to walk until it had gone. I followed the Cam downstream from Jesus Green, passing various interesting buildings, and then out onto Stourbridge Common.

It was all a bit of an adventure at the time, though now with greater familiarity (and with the first two miles up to the Green Dragon Bridge at Chesterton being half of my usual morning run) it seems a little meagre as walks go. Anyway, following the river I eventually came to the village of Fen Ditton, with St Mary sitting proud on a rise overlooking the flood meadows.

This is by far the nicest way to approach Fen Ditton: the other option is to go through the gloomy suburbs of north-east Cambridge, which tends to blur the distinction between town and village and disguise the extent to which the latter has managed to maintain its character. It's a pleasant little place with a couple of pubs, a shop, a post-office and lots of nice houses. To the east of the church is a row of old almshouses, and to its north is a fine Georgian brick house, presumably once the rectory.

Sadly, the proximity to some of the less salubrious parts of Cambridge means that St Mary is kept locked, with no indication of a keyholder. So, I have several times walked or ridden past the church without entering. In 2006, though, I went back with Mark - and being his usual courageous self, he went to find the rectory and acquire a key.

While he did that, I stood in the churchyard, and watched a race down on the river below. St Mary overlooks one end of the main rowing course on the Cam, and marks this with its weathervane: rather than the usual cockerel, there is a Blues boat that sits atop the little tower. I rapidly grew bored with watching the boats, though - rowing is such a dull sport, after all - and turned to a more detailed examination of the church itself.

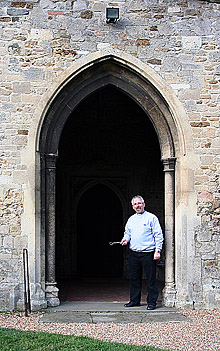

The exterior isn't promising: a thorough Victorian restoration has left it looking so pristine and sterile that I wasn't sure whether there were any old bits left at all. As it happens, most of it is: 14th and 15th century nave, aisles and clerestory, a big 14th century south porch, and a Decorated chancel. The tower - which is rather squat and plain - was

originally 13th century, but was completely rebuilt (albeit using the original material and replicating the original design) in 1881.

The porch is a tall one, open up to the full height of the aisle. There are benches on either side, and a neat Perpendicular south door within, set into what looks like a bigger and older opening. Inside, steps into a pleasant enough space. The nave is of four bays, with 15th century arcades and clerestory. The piers are of a familiar design, following the profile of the wall on the north and south faces, and with half-shafts in the thickness of the wall facing east and west supporting some moulding.

More unusual is the west end. The aisles clasp the tower, which means that there are open arches to the north, south and east. The eastern one is the most elaborate, with some nailhead decoration on the outermost line of moulding. This is echoed in the west wall, though there the arch is blind, filled in with a wall containing only a lancet window, and no door. This was rather a conundrum to us: it's unusual for Early English work (as the tower was, before its reconstruction) not to have a west doorway, and why would they have gone to the trouble of building such a stately arch only to fill it in? Mark's guess - and I'm inclined to agree with him - is that there was originally a Galilee porch here, a reduced version of the design seen at nearby Bottisham.

Up at the east end of the nave, we found another architectural fossil, in the form of the rood stair. The lower doorway is now tucked behind the pulpit, but the door at the top is open, and surprisingly high. The rood screen must have been very grand. Sadly, it is no more - though much to our horror we discovered that it had only been removed in 1881. Why on earth did they get rid of it? Another doorway opens from the staircase onto the aisle, and suggests that there were also parclose screens.

The south aisle has a little altar at the east end, and judging by the rather stout Virgin appearing in the stained glass in the window above it, this is now the Lady Chapel. It must always have been a chapel of some sort, since the window is framed by a pair of matching niches, with slightly ogeed cinquefoil arches over the top. The walls around look suspiciously blank, and I suspect that there were originally big canopies over the top - not that anything survives now. There is also a piscina in the south wall, in similar design. Above it, on a window ledge, there is a nice little collection of carved stonework, including a piece of frieze with two angels, and an enthusiastically grinning king's head with very curly hair. There is more of the angel frieze sitting in the north aisle, with the remains of some red and gold paint, as well as a delicate leafy capital. The quality of carving - especially of the angels - is surprisingly fine, but the stone used was such soft clunch that it all has the look of slightly melted wax now.

The chancel arch is plain and tall, as is the chancel itself. This was supposedly enlarged by Alan of Walsingham, who is more famous for having overseen the building of the Octagon at Ely Cathedral. There are no such flights of architectural genius here, though it's pleasant enough. The south and east walls are decorated with a string course that frames the altar and dips below the south windows. The line is lost on the north wall, if it ever existed, but there is a disused doorway that presumably once led through into a vestry. The stone used to block it seems to have been laid in rather a hurry, and the haphazard arrangement makes it look like a slice cut through some deep geological strata.

Next to it is a monument to the Wylie family, which is rather elegant: two black marble slabs covered in writing, with the top one supported by grey marble verticals, each carrying a shield. Finally, the east window is worth a look: the glass is Victorian (but a decently non-sentimental Passion sequence) but the tracery is rather sophisticated Decorated stuff, with interesting shapes formed by the looping, sweeping stone. Like the rest of St Mary, it doesn't exactly set the pulse racing; but it's interesting enough. What a pity that it's not easier to get in.

St Mary is kept locked, with no information about keyholders.